WORDS: Kerra-Lee Wescombe, Director Connect.Ed

Our brains are amazing. They control our basic life functions (which keep us alive), whilst helping us to understand and engage with the world around us.

Children’s brains are still developing, which is why they often find it difficult to manage their ‘big feelings’. Having a basic understanding of the various structures and functions within the brain can help us to understand children’s behaviours and manage those big feelings more effectively. Whilst neuroscience can seem complex and overwhelming, Dan Siegel (2012) explains it in a simple way, using the hand model of the brain.

Brains develop from the bottom up

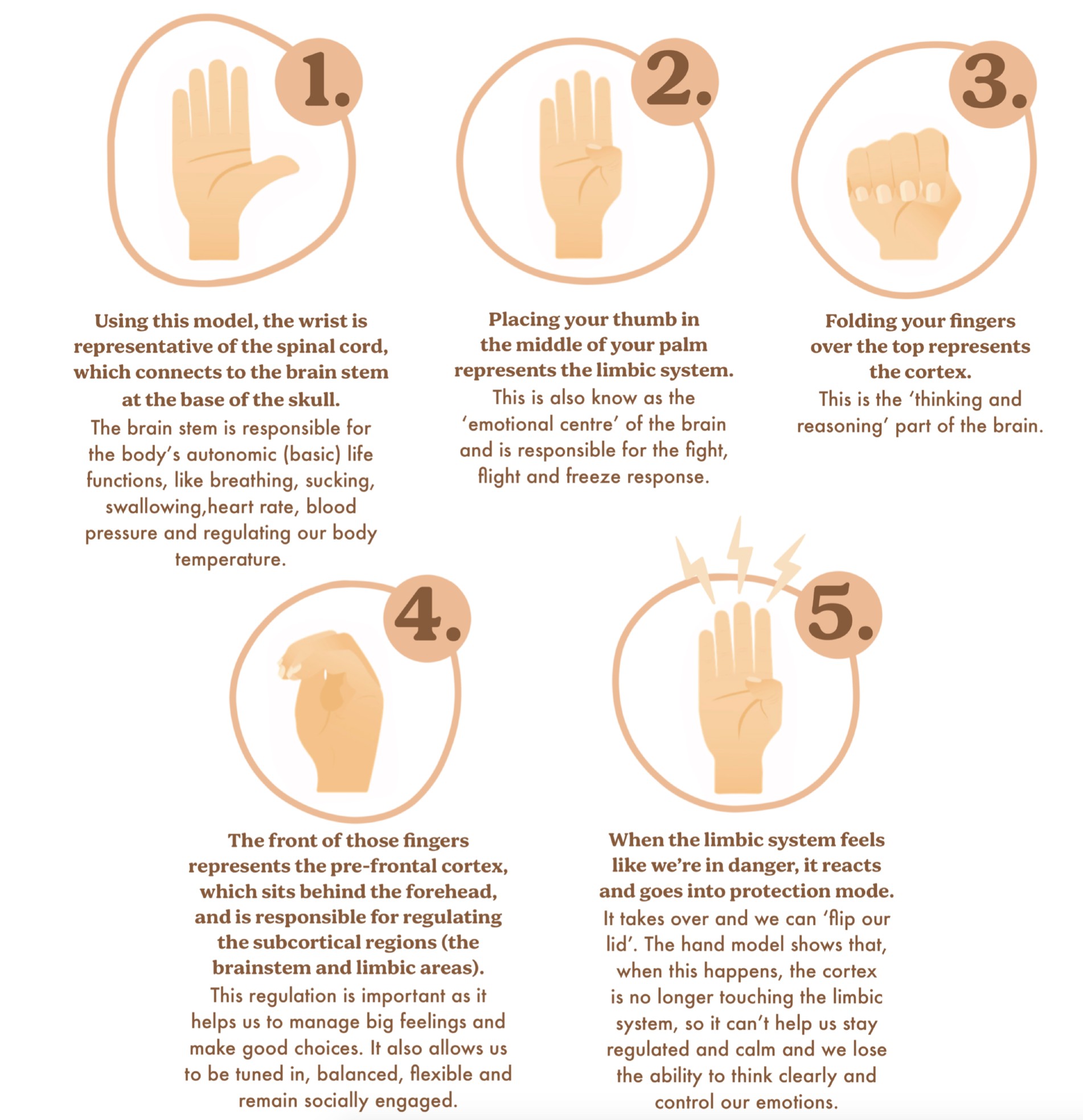

Human brains develop ‘neurosequentially’, which is a fancy way of saying that they develop from the bottom up. The first part of the brain to develop is the brainstem which is responsible for basic life functions, such as breathing, sucking, swallowing and regulating our body temperature. Using the hand model of the brain, the wrist is representative of the spinal cord, which connects the brainstem to the base of the skull.

If you place your thumb in the middle of your palm it represents the limbic system, which is also known as the ‘emotional centre’ and is responsible for the fight, flight and freeze response.

Folding your fingers over the top represents the cortex, which is the ‘thinking and reasoning’ part of the brain. The front of those fingers represents the prefrontal cortex, which sits behind the forehead, and is responsible for regulating the subcortical regions (the brainstem and the limbic areas). This helps us to manage big feelings and make good choices. It also allows us to be tuned in, balanced, flexible and remain socially engaged.

When all of these parts of our brain are connected and working together, we can remain calm and connected with others but, when the lower parts of the brain feel overwhelmed, they take over and we can ‘flip our lid’. The hand model shows that, when this happens, the cortex is no longer touching the limbic system, so it can’t help us stay regulated and calm. Essentially, we lose the ability to think clearly and control our emotions which means we cannot reason or learn. In situations such as this, children might be viewed as aggressive, disruptive or defiant.

Emotions through the lens of Neuroscience

When we view emotional dysregulation through the lens of neuroscience (using the hand model of the brain), we can recognise when children have ‘flipped their lid’. When they’re in this dysregulated state, using language and reasoning is often ineffective as they are neurobiologically unable to access the thinking part of their brains.

Prioritising co-regulation over self-regulation

When children have flipped their lid, they may also be unable to self-regulate. Instead, it’s important to prioritise co-regulation.

When we expect a child to self-regulate, we’re essentially expecting them to access their ‘thinking brain’ when they’re dysregulated. But we’re not born with these skills. Young children do not have the biological capacity to self-regulate, so they are reliant on the adults around them to co-regulate.

The capacity for self-regulation is built through connection and repeated experience of co-regulation. A caregiver’s capacity to help a child regulate their responses reinforces neuronal connections that support the child to manage stressful experiences in the future. This supportive process occurs within the context of caring relationships (both with parents and Educators), whereby the adult provides regulatory support when the child is emotionally overwhelmed.

Once this has been repeated (over and over again), the skill is internalised and forms the neural network necessary for self-regulation.

But, what happens when the adult is dysregulated too?

A dysregulated adult cannot co-regulate a dysregulated child, which is why it’s so important for us to take care of ourselves too. So, when these tricky situations arise (and they will!), we can help calm their chaos, not join it.

Kerra-Lee, Director of Connect.Ed has completed a Bachelor of Psychological Science, a Graduate Certificate in Developmental Trauma, a Graduate Certificate in Education and a Graduate Certificate of Therapeutic Child Play. Her work is strongly influenced by interpersonal neurobiology and she is passionate about incorporating body-based interventions to facilitate brain-body connection, particularly when supporting children to develop regulatory functioning. She is also mama to new baby Harlem.